A new polymer sunscreen creates a physical barrier to UV light without the chalky look.

Skin cancers are linked to tens of thousands of deaths each year. Sunscreen saves lives by protecting the skin from harmful ultra-violet (UV) rays. But there are niggling doubts about their safety because of evidence, albeit limited, that sunscreen may disrupt hormones, cause lymphatic and blood cancers1 and bleach coral.2 A new polymer-based sunscreen that remains on the skin surface developed by Tsinghua University researchers may provide a route to side stepping those concerns.

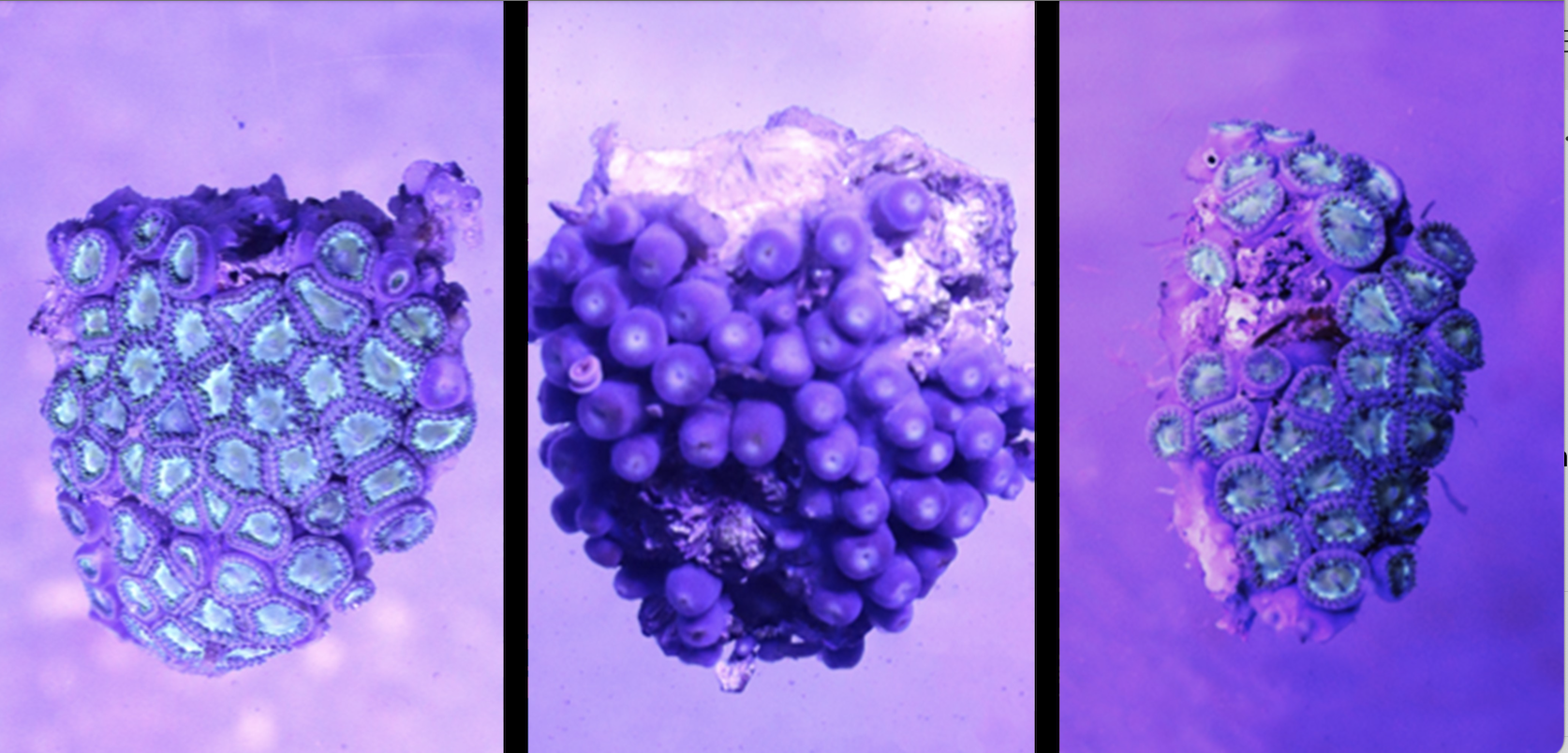

The effect of the presence of UV filters – P3, oxybenzone and avobenzone – on Palythoa sp. after two weeks of exposure.

Today’s chemical sunscreens depend on small organic molecules that absorb UV, such as oxybenzone, avobenzone and octinoxate. That’s a potential problem because the molecules are absorbed by the top skin layer, explains Lei Tao, lead author of the study and an associate professor at Tsinghua’s Department of Chemistry.

Once inside the body, these small molecules may lead to endocrine disruptions2 that harm fertility and reproductive organs3 and increase the risk of cancer,1 although various international government agencies, including the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), have declared them safe for human use.

What’s more, an estimated 14,000 tons of sunscreen enter waterways each year globally. In situ and laboratory research suggests that the small organic molecules in sunscreen could be toxic to,4 or promote viral infection5 in, corals. This results in bleaching.

“We need new sunscreens that protect both humans and the environment,” says Tao.

Surface sunscreen

At the moment, the only alternative to chemical sunscreens based on small organic molecules are sunscreens containing minerals like zinc oxide that sit on the skin and physically block rays. These aren’t absorbed into the body, but leave a white caste that puts people off using them.

To solve the problem, Tao and his team developed a polymer sunscreen made up of large molecules that don’t penetrate the skin.6 This polymer sunscreen sits on the skin like physical sunscreen, but without the white caste, says Tao.

In mouse experiments, the new polymer sunscreen blocked UV more effectively than SPF 50+ commercial sunscreens. Mice wearing Tao’s new ‘polymeric’ sunscreen had significantly less sun damage after being directly exposed to very strong UV light for six minutes, roughly equivalent to the exposure one might expect in Australia across the course of 5–10 years, compared to mice wearing commercial SPF 50+ sunscreens.

When the team exposed corals to the new polymer sunscreen, the corals retained their colors for more than 20 days. Corals exposed to the active ingredients in commercial chemical sunscreens were completely bleached within six days.

Associate professor Lei Tao is from Tsinghua’s Department of Chemistry.

A colorful future

But there are still hurdles to overcome, says Tao. For example, the sunscreen polymer is water soluble so it may not be practical at the beach, he says.

The researchers also need to address concerns about the environmental impact due to the new sunscreen’s lack of biodegradability. Tao and his colleagues are now exploring different polymerization methods that combine biodegradable molecules with UV-shielding molecules in an attempt to enhance biodegradability.

The mechanism behind why the corals react to other sunscreen ingredients, but not to the new polymeric filter, also needs to be explored, Tao says.

Nonetheless, he is excited about the potential impact of his new polymetric sunscreen on human and coral health. “Such sunscreen could have been invented already if more chemists had travelled to the beautiful Great Barrier Reef!” he says.

References

1. Pal, V.K., Lee, S. & Kannan, K. Occurrence of and dermal exposure to benzene, toluene and styrene in sunscreen products marketed in the United States Science of The Total Environment 888, 164196 (2023) doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.164196.

2. Golden, R., Gandy, J., & Vollmer, G. A review of the endocrine activity of parabens and implications for potential risks to human health. Critical reviews in toxicology, 35(5), 435–458 (2005) doi: 10.1080/10408440490920104

3. Krause, M., Klit, A., Blomberg Jensen, M., Søeborg, T., Frederiksen, H., Schlumpf, M., Lichtensteiger, W., Skakkebaek, N. E., & Drzewiecki, K. T. Sunscreens: are they beneficial for health? An overview of endocrine disrupting properties of UV-filters International journal of andrology 35(3), 424–436 (2012) doi:10.1111/j.1365-2605.2012.01280.x

4. Hansel, C.M. Sunscreens threaten coral survival Science 376, 578-579(2022) doi:10.1126/science.abo4627

5. Danovaro, R., Bongiorni, L., Corinaldesi, C., Giovannelli, D., Damiani, E. et al. (2008). Sunscreens cause coral bleaching by promoting viral infections Environmental health perspectives 116(4), 441–447 doi: 10.1289/ehp.10966

6. Zeng, Y, He, X., Ma, Z., Gou, Y., Wei, y. et al. Coral-friendly and Nontransdermal Polymeric UV Filter via the Biginelli Reaction for In Vivo UV Protection Cell Reports Physical Science 4 (3), 101308 (2023) doi: 10.1016/j.xcrp.2023.101308

Editor:Guo Lili